Minneapolis, the Mill City, held the title of the “Flour Milling Capital of the World” for half a century and spurred innovations in technology, business, and culture that helped the city blossom.

Minneapolis Flour Milling Boom

The birth of the flour-milling industry in the mid-19th century was the second act in the industrial drama that took place at St. Anthony Falls and established Minneapolis as a major US city. While lumber sawmills arrived first in the 1840s, they were supplanted within decades by the flour mills. It was the extraordinary power-generating potential of the falls' 50-foot drop that brought the two industries to Minneapolis, though the heyday of flour milling outlasted that of saw milling by several decades. In 1880 and for 50 years thereafter, Minneapolis was known as the "Flour Milling Capital of the World."

The city grew up around the mills. In 1870, the population of Minneapolis was 13,000 and just 20 years later it had grown to nearly 165,000. Immigrants were part of this enormous population influx during the period, and they kept the farms, railroads, and mills of Minnesota running. Businesses supporting milling, such as bag making, barrel making, and iron works, also employed the city's new citizens.

The mills received grain via rail lines stretching across the Northern Plains grain belt into the Dakotas and Canada. Trains then carried the milled flour to Duluth and to eastern US destinations for export and domestic distribution.

At the industry's peak, more than 20 stone flour mills stood along a covered canal, flowing with water drawn from the river above the falls. When the Washburn A Mill reopened in 1880, two years after the catastrophic explosion, it was the most technologically advanced and the largest in the world. At peak production, it ground enough flour to make 12 million loaves of bread in a day. This level of production was unheard of, as most mills at the time were still smaller operations serving the towns and cities in which they were located.

In the industry's early days in Minneapolis, almost all sales were of "family flour," used in home baking and sold in 196-pound family barrels. It wasn't until later that the barrels were replaced by 100-, 50-, and 25-pound cotton or jute sacks.

Home baking declined, however, as more people moved from farm to city. But as they did, the commercial baking industry grew. In 1900, only five percent of bread consumed was bakery-made. By the time the US entered World War I in 1917, bakeries were making 30 percent of the nation's bread.

As flour milling reached its peak in Minneapolis in the early 20th century, a revolution in marketing and advertising arose out of a need for flour manufacturers to differentiate products that were essentially the same: the grain came from the same fields in western Minnesota and North Dakota, and it was milled on the same types of machines using the same techniques. So manufacturers got creative with their campaigns; General Mills, for example, introduced Betty Crocker in 1921, today an icon in the history of marketing.

The flour milling complex spawned a host of innovations in manufacturing and processing. The leaders of the Minneapolis milling industry, including the Washburn, Crosby, and Pillsbury families, invented equipment and techniques that both improved the quality of flour and increased production efficiencies. White flour, something once seen as a luxury for the rich, was brought to the masses. New flour-based products, such as cake mixes, created an entirely new market for flour.

As the flour industry evolved, so did the businesses that were a part of it. Cadwallader C. Washburn had already teamed up with John Crosby in 1877 to form the Washburn-Crosby Company, best known for their Gold Medal Flour brand. In 1928, the Washburn-Crosby Company merged with 28 other mills and was renamed General Mills. Eventually, in 2001, General Mills bought Pillsbury, finally uniting Minnesota’s two largest flour manufacturers.

After World War I, the milling industry in Minneapolis began to decline. Federal import-export regulations led mills to move to cities better situated to process Canadian wheat. In 1930, Buffalo, New York, supplanted Minneapolis as the nation's flour-milling capital, producing 11 million barrels to Minneapolis's 10.8 million annually.

As the industry moved out of Minneapolis, the old mills fell into disuse. Many were abandoned and subsequently razed. The Washburn A Mill closed in 1965. The Pillsbury A Mill was the last riverfront mill to shut down in 2003.

While the mills have left, the impact that the milling industry had on Minneapolis is still felt today. The industries that grew up around the mills — marketing and advertising, banking, legal services, education — are as significant to the city’s identity today as the mills once were.

For further research

-

Forests, Fields, and the Falls: Connecting Minnesota

Introduces students to Minnesota's lumbering, sawmilling, flour milling, and farming history through four first-person narratives presented in a comic-book format. -

Minneapolis Flour Milling during WWI

MNopedia

The Minneapolis flour-milling industry peaked during World War I when 25 flour mills employing 2,000 to 2,500 workers played a leading role in the campaign to win the war with food. Minneapolis-produced flour helped to feed America, more than four million of its service personnel, and its allies. -

Betty Crocker

MNopedia

From the often-reissued Betty Crocker Picture Cookbook to the iconic red spoon logo that bears her signature, Betty Crocker is one of the most recognized names in cooking. It comes as a surprise to some that “America’s First Lady of Food” is, in fact, fictional. -

Pillsbury Bake-Off Contest

MNopedia

In 1949, the Pillsbury Company in Minneapolis celebrated its 80th anniversary. To promote Pillsbury’s Best Family Flour, it created the Grand National Recipe and Baking Contest, later named the Bake-Off, to discover the country’s best amateur bakers and recipes. The winning recipes were placed in Pillsbury flour bags as an incentive for consumers to purchase one of Pillsbury’s premier products. -

Flour Power: The Significance of Flour Milling at the Falls (PDF)

Minnesota History Magazine, Spring/Summer 2003

Explores the ties Minneapolis milling had with the globalization of the United States economy. -

"To the Markets of the World": Advertising in the Mill City, 1880-1930 (PDF)

Minnesota History Magazine, Spring/Summer 2003

Advances in advertising, branding, selling and creating demand for named flours.

In the MNHS shop

-

Selling the Mill City: A Postcard Book

Mills found themselves in fierce marketing battles to win consumers over with their various flour brands. This book features 30 black-and-white tear-out postcards of historic images of advertising art from the mills in the Mill District

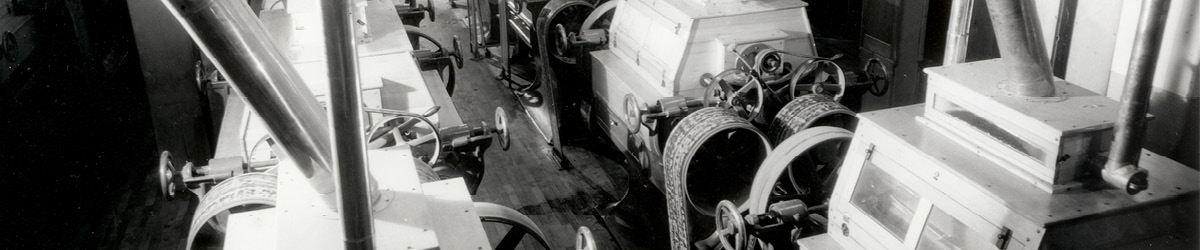

The Minneapolis flour milling district, circa 1920. The Minneapolis flour milling district, circa 1920Source: MNHS Collections.